Water

Episode 3 | 53m 18sVideo has Closed Captions

As our oceans change, can science, nature and tradition prepare us for a fast-changing future?

With our warming planet altering our oceans, an extraordinary team of marine experts from Antarctica to Australia, and from Florida to New Zealand, dive into how science, nature, and tradition can prepare us for a fast-changing future.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Water

Episode 3 | 53m 18sVideo has Closed Captions

With our warming planet altering our oceans, an extraordinary team of marine experts from Antarctica to Australia, and from Florida to New Zealand, dive into how science, nature, and tradition can prepare us for a fast-changing future.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Dynamic Planet

Dynamic Planet is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Buy Now

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship[Engine roaring] [Dogs barking] ♪ Molina: Y, pues, en las noches, como a las 8:00, de las 8:00 en adelante, pues salimos a hacer el recorrido, el monitoreo.

[Speaking in Seri] El chiste es trabajar toda la noche porque tenemos... pues, para ganarle a los depredadores, llegar antes que ellos.

♪ Si nosotros tardamos mucho en llegar, a veces nos ganan los coyotes.

♪ Pasa tú.

Narrator: Meet the Comcáak Turtle Guardians.

They're searching for sea turtle nests.

♪ Molina: Sí es... Sí.

Y, si tenemos suerte, si encontramos uno, pues tenemos que, bueno, sacar los huevos, contarlos.

Narrator: Sea turtles are sacred in the Comcáak Indigenous culture in northern Mexico.

The turtle guardians are doing all they can to protect them.

Molina: Y fue el nido número uno que encontramos en la noche, que fueron 107 huevos.

Narrator: The eggs will be reburied in a safer spot.

But the unborn turtles and their ocean home face a challenging future as the world heats up faster than at any time in human history.

[Engine roaring] [Fire crackling] In this epic new series, we explore the extremes... Man: Careful!

Careful!

Narrator: on all 7 continents.

[Clanking] Meeting people standing in the face of change.

And revealing how science... Woman: Whoa!

Narrator: nature... [Trumpets] and Indigenous knowledge can prepare us for a fast-changing future.

This time we explore the oceans on our dynamic planet.

♪ ♪ The oceans are Earth's life support system.

They cover almost three quarters of our planet, absorb vast quantities of heat and carbon, and provide half the oxygen we breathe.

And don't forget all the food and work.

Over a third of us rely on the sea to make a living.

But as we alter our climate, the ocean's chemistry and temperature are changing with major and sometimes surprising consequences.

♪ El Desemboque is a remote village in northern Mexico.

Located where the Sonoran Desert meets the sea.

Molina: Yo creo que es muy importante cuidar el mar porque, para la comunidad, toda su vida ha trabajado en el mar.

[Dog barking] Narrator: The Indigenous Comcáak people that live here have a deep ancestral connection to the ocean.

In their origin stories, a sea turtle helped form the Earth.

Molina: Es una de las especies que es sagrada para la comunidad.

Y es de suma importancia que no, o sea, que no estén... que no desaparezcan por completo.

Narrator: Sea turtles have been around since the time of the dinosaurs.

But hotter conditions now threaten this ancient species.

Molina: Y, pues, a lo que nosotros nos preocupa es que, en estos últimos años, ha aumentado más el calor, se han visto más huracanes, más tormentas, y el agua está... el mar está subiendo demasiado y eso hace que... que nos afecte a todos.

Narrator: To improve the turtles' odds of survival, their eggs are moved to a hatchery where they're protected from increasingly frequent storm surges that wash away the nests.

Pues aquí en la comunidad trabajamos más con las tortugas golfinas.

Que son los que más llegan a desovar aquí en nuestra playa.

Narrator: The olive ridley is the world's most abundant sea turtle.

But their numbers are falling drastically.

Yasmin has come to check on a nest that was moved here over a month ago, an extreme measure to save the baby turtles.

Hola, Jesús.

Hola.

Ya salieron.

Y el calor no ha aumentado, ¿no?

No.

Por eso están saliendo.

♪ Haciendo calor, pero ahorita está... está nublado.

Les va a ayudar con lo nublado, creo.

Ajá, sí, lo más probable.

Sí.

A ver si llegan los demás compañeros.

Nos preocupa mucho con el tema del calor, que ha estado aumentado más y más porque eso está... Bueno, eso tiene un gran impacto sobre las... sobre las tortugas de nuestro trabajo.

Narrator: A turtle's sex is determined by the warmth of the sand around the nest.

The hotter it gets, the fewer males will hatch.

Above 91 degrees, the hatchlings will almost all be female and may struggle to find a breeding partner.

Bad news for a species already in decline in a warming world.

Molina: Lo que nosotros hacemos es poner una media sombra en el corral, en el corral de incubación para proteger a los nidos más que nada de la temperatura y que no esté tan caliente la arena.

♪ Yo creo que el trabajo que estamos haciendo es... Creo que es muy importante porque, pues, más que nada para los niños, para la generación que viene, que aprendan sobre lo que es la importancia de proteger las tortugas marinas.

[Cheering] Narrator: Sea turtles help safeguard the overall health and resilience of marine environments.

And, by keeping the reefs healthy, they ensure a bountiful supply of fish for the Comcáak people.

♪ Molina: Uno de los riesgos que tiene la tortuga al momento de nacer, al momento de ser liberada, es que tiene que enfrentarse a su nuevo mundo, bueno.

O, pues, tienen, pues, sobreviven, pues, poquito por ciento, ¿no?

♪ [Singing in Seri] Molina: Y, pues, cada año liberamos como alrededor de 7000 o 6000 tortuguitas.

Y, pues, para mí es un orgullo saber que... que, por lo menos, estamos dando un pequeño porcentaje de que se aumente más... más la población de tortugas.

Narrator: The Turtle Guardians and many other Indigenous groups worldwide make a small but significant difference.

But rising temperatures have complex implications such as affecting a turtle's sex.

It's a reminder that changes in one place can have surprising and far-reaching consequences.

♪ Wellner: We are on a research vessel, an icebreaker headed south.

We want to be up as close to the Antarctic continent and ice sheet as we can so that we can see exactly where the ice is changing.

♪ We work in places where no vessel has been before.

And what that means is that we're often working in ocean that was ice a year ago or a decade ago.

We work 12-hour shifts, 12 on, 12 off, 7 days a week.

Narrator: More people have traveled to space than some of the places this multinational team will visit on their voyage.

Their work will provide a crucial new understanding of how melting ice in Antarctica will affect sea levels worldwide.

They're here to study Antarctica's infamous Doomsday Glacier.

Thwaites Glacier is bigger than the entire state of Florida and it's melting fast.

Wellner: The reason there's so much interest in this area is Thwaites acts sort of as a cork to hold back what's behind it.

Narrator: Inland, behind Thwaites Glacier, lies the West Antarctic ice sheet.

There's enough ice here to raise global sea levels 16 feet, flooding all the world's major coastal cities.

And the cork is coming loose.

Wellner: If we lose Thwaites, then we lose the cork in the bottle that's holding the ice back behind it.

And, in that case, then we could enter a place where more and more ice is flowing into the ocean.

Narrator: The main threat is where Thwaites meets the sea.

At the surface, the salt water is too cold to melt the ice.

But, down deep, it's a different story.

♪ The door will open and they will assess if there's too much water coming in.

Narrator: Below 1,000 feet, there's a current of warm water that might be melting the ice at the base of the glacier and weakening the cork.

Wellner: By warm water, we don't mean bath water, but simply water that is above zero.

And, if that warm water reaches the base of the ice, it is melting the ice from the underside.

[Man speaking on radio] Narrator: The team measures water temperatures at different locations and depths.

OK, Sam, let's increase speed to 4.0.

Sam: 4.0!

Narrator: But there's thick sea ice right next to Thwaites itself.

The team can't get close enough to take the crucial temperature measurements where the glacier meets the ocean.

Head back.

Blow pipe.

Warm box.

Our gear.

It's all there?

Narrator: But extraordinary challenges require extraordinary solutions.

Boehme: We are responsible for getting the oceanographic data in front of Thwaites Glacier, and we do that with totally different means from traditional ship-based measurements.

What we do here is we take elephant seals.

I think we should stop at one point.

Narrator: Elephant seals are the biggest and deepest diving seal species.

The largest can weigh twice as much as the average car.

Getting up close takes careful planning.

If we use a dart, we have to make sure for 10, 15 minutes that this seal is not going into the water.

And he seems to like moving.

♪ [Penguins honking] ♪ [Grunting] [Barks] Everybody knows what they have to do?

Man: Yeah.

Head bag.

I'll get the drugs.

♪ Narrator: The sedated seal is fitted with miniature oceanographic sensors.

They'll record the location, depth, and water temperature whenever the seal dives.

[Sea elephant grunts] Boehme: The warm water down here is at depth so we need something that goes deep in the water and these seals do that.

Narrator: Elephant seals act as living submarines, diving as deep as 5500 feet and staying under the ice for up to 90 minutes.

Multiple seals are tagged to create a detailed record of the increasing sea water temperature at the base of Thwaites Glacier.

Boehme: This morning, I think we put 3 tags out, which is a really good day for us.

Narrator: Highly fashionable.

This high-tech headgear will fall off harmlessly after recording a year's worth of vital data.

Boehme: Getting the seals to help us to collect data is really amazing in terms of oceanography.

It gives us a really nice overview of what the ocean does here in front of Thwaites Glacier.

♪ Narrator: Over 150 billion tons of ice melt into the ocean from Antarctica each year.

Enough to fill 60 million Olympic swimming pools.

As the rate of melt increases, the impact on coastal communities will grow and, because of the way the Earth's gravity and rotation affect the oceans, Florida is disproportionately in the firing line.

♪ [Horn honking] ♪ Looks like there's some sandbags in front of that.

In front of that Ferrari store.

Demayo: Yeah, this area floods pretty bad.

Narrator: Low-lying Miami is particularly vulnerable to rising seas.

A few times each year, the orbits of the sun, moon, and the Earth align, producing extra-high king tides that flood parts of the city.

It's a taste of what's to come not just here, but in coastal cities worldwide.

It's only a couple of inches, but the entire ocean is rising and those little inches in time become this significant impact event.

Narrator: Miami urban planners are bracing for sea levels to rise two feet in the next 35 years.

Regular inspections of the city's flood defenses are crucial.

♪ Demayo: I haven't seen the water come in with this kind of speed in this location before.

There's not even a seawall here.

We just have an embankment which probably, at one point, was enough to keep the water out of this area.

So the pump is essentially actively helping the stormwater system.

They turn it on when we have the tide events at these peak moments to help alleviate the flooding on the street.

There's no way that pump is going to be able to act against the bay.

♪ Narrator: Water is also flowing in hundreds of yards up the street.

Oh, wow, the pressure is so strong.

Yeah.

8.5.

Got it.

OK, this is pretty salty.

Narrator: Sea water is infiltrating the stormwater system.

Another weak link in Miami's defenses.

But it's not just people and their homes that are threatened as sea levels rise.

For some species, it's a matter of life and death.

Crazy.

♪ Killam: Key deer are wild animals, but they don't get frazzled by people, you know, being next door.

No begging.

This is why I don't bring the telephoto.

Nope.

No mooching.

Narrator: Kristie Killam is a recently retired ranger at the National Key Deer Refuge on Big Pine Key.

Killam: Now that I'm retired, I'm an amateur nature and wildlife photographer.

I kind of like the messaging of my photographs to be all about conservation.

Narrator: Florida's iconic key deer are her favorite subject.

But their future is uncertain.

Fewer than 1,000 remain.

The deer are only found here, on the lower Florida Keys, part of a chain of coral islands that sit just 3 feet above the steadily rising sea.

You know, as a biologist, I always look at things from the wildlife and nature perspective, but, as a person who lives here and has skin in the game and... and cares about the community, uh, it's... it's a little frightening, I have to say.

Narrator: The key deer rely on natural watering holes, but the fresh water they contain is threatened.

Killam: Things like sea level rise and hurricanes and the impact of king tides even can actually start these things transitioning to a more brackish and saltwater type place.

So, if these get too salty, then key deer are in big trouble.

Narrator: The sea is already destroying prime habitat.

Killam: I've only been here observing things for the last 15 years full time.

But you can see changes happening.

You can see that subtle rises in sea level are having drastic impacts.

It's sad.

It makes me feel sad.

Big Pine Key and Little Pine Key were named for these pine forests, which are endangered habitats themselves.

And the pines are dependent on fresh water.

So, as sea level comes in, you see plants giving way and dying.

♪ You see mangroves taking over habitats where there's pine tree stumps.

It's kind of a visual warning of what the future might hold.

♪ Narrator: When mangroves move in, land and fresh water are lost.

The deer are already on the brink of extinction.

A shift in climate may push them over the edge.

Their plight serves as a warning to other vulnerable coastal communities, both animal and human.

Killam: I think, for me, an impactful image of a key deer is one that kind of tells the story about their struggles for survival.

It does give you pause to think, "Wow, "what does this look like down the road, 50, 100, 200 years from now?"

Narrator: In the keys, mangroves are a worrying sign of change.

But, back in Miami, they could be an important part of the solution.

The whole area once had lots of mangrove swamps, reducing the impact of storm surges and flooding.

Good.

Narrator: Many have been removed over the last century, but Aaron and Ian would like to see them make a comeback.

I would say mangroves are an incredible solution for many things that help provide critical habitat for fisheries and bird populations.

They help sequester carbon.

There's a whole slew of benefits to mangroves.

Wow!

Narrator: Mangroves are found in over 100 countries worldwide.

They're a powerful natural climate solution, capable of storing 4 times more carbon per acre than tropical rainforests.

But well over one million acres have been destroyed this century alone.

And here in Miami, with its multimillion dollar waterfront views, not everyone loves mangroves.

Demayo: Mangroves block the view of the water and a lot of people want the view of the water, so that's a major challenge to deal with.

Narrator: But, as the oceans get warmer and the severity of storms increases, mangroves could be a vital defense.

Demayo: If you have a stand of mangroves, they provide this incredible natural buffer that will help mitigate and reduce storm surge up to 90%.

It's mind-boggling that there's this short-sightedness of making a quick buck on the real estate that's right on the coast because it's the most desirable, instead of really putting the resources, energy, and efforts towards these solutions that we are totally capable of creating.

Narrator: Many coastal cities worldwide are running out of time to upgrade their failing defenses.

As the mercury rises, hurricanes and storm surges are happening more often.

Sea level rise will make the problem worse.

But how much higher could the water go?

♪ The team on the Antarctic icebreaker have now been at sea for nearly two months.

It's approaching the fall.

The polar nights start getting longer and temperatures plummet.

But the work continues in shifts 24 hours a day.

Wellner: We hope that our work will eventually feed into a better understanding.

Not just of how much global sea level might change, but how fast can that happen.

I think it's going to be... Narrator: To find out more, the team takes sediment samples from the seabed.

It's a tough and dangerous job.

Each 10-foot core records variations to the rate of ice melt, going back hundreds of years.

OK. Nice.

Narrator: Understanding past changes will help the team anticipate how things might change in the future.

Wellner: One thing that we look for is evidence of meltwater that might be coming from the ice.

Meltwater carries a distinct sediment type.

We look for that and see if we can see evidence that meltwater has been flowing in this region.

Our initial observation by eye suggests that we are finding that sediment and a signal of meltwater.

Narrator: The meltwater points to dramatic changes in climate across the region.

The team samples are from the seabed near Pine Island Glacier, Thwaites' massive neighbor.

It's enormous, nearly the size of Great Britain.

And it's the fastest melting glacier in Antarctica, responsible for a quarter of the continent's ice loss.

♪ But the changing conditions here also offer new opportunities.

Wellner: Since we set sail, Pine Island Glacier has calved a couple very large icebergs.

One of them was large enough to get a name and it's called B49.

It's about twice the size of Washington, D.C. Narrator: The team will be the first to explore the area exposed by the iceberg.

♪ The trip allows them a rare opportunity to be the first people to set foot on a newly emerged island.

♪ [Cheering] Wellner: Yeah, moments like that, where we get to jump onto rocks that only seals have been on before... um, is exciting.

Narrator: Rock samples will help the scientists learn more about the history of Antarctica.

Wellner: If you want to put that in now.

Narrator: Data from the icebreaker expedition will help predict how quickly Antarctica's glaciers might melt.

The rate of melt will speed up dramatically if we don't reduce carbon emissions fast.

What we do in the next few years will have implications for years to come.

Wellner: One of the themes of the work is how much, how fast.

Will we have one meter of sea level rise in the next hundred years?

I personally think that puts too much emphasis far out into the future.

Because, for many people, one centimeter will be a big deal.

Narrator: This is especially true in the countries least able to adapt.

♪ Low-lying Bangladesh has already experienced devastating floods, displacing millions of people.

And entire island nations, like Kiribati, are at the risk of being lost forever.

But rising seas aren't the only challenge we face.

Some parts of the ocean are facing multiple climate threats.

But now a group of conservationists are in a unique mission to save one of the most vulnerable ecosystems of all.

♪ Veron: The Great Barrier Reef is the most spectacular place on the face of this planet.

The grandeur and the size of the beauty is beyond description.

♪ I must be a bit biased, but there is nothing like a coral reef.

I'm happiest just being out on the reef all day long.

It's my home ground.

Narrator: In the world of marine science, Charlie Veron is known as the Godfather of Coral.

Which is why marine conservationist Dean Miller has joined him on today's special mission.

I'll help you get yours on first, Charlie, and then I'll put my tank on.

Miller: Charlie literally wrote the book on corals.

There is probably no one on earth that has dived in more coral reef locations and as many times as Charlie has.

OK, Charlie, you're good to go.

If you want to go sit on the bottom, we'll come and meet you.

All good.

You're a good man.

Thank you.

♪ Miller: Working with Charlie underwater is hugely exciting to me.

He's collected corals and he's described them and he's named 20% of the world's species.

To see Charlie identify corals to a species level is phenomenal.

There's only about 5 people on the planet that can actually do this.

Narrator: But today's job is about more than just identifying coral.

♪ The team is attempting to save the Great Barrier Reef before it's too late.

Miller: Since 2016, we've had 4 mass bleaching events in 6 years and, in that short time frame, we've seen devastating changes take place.

And that's because of climate change and the increase in sea surface temperatures.

The corals can't go anywhere, so they literally bathed in, you know, water that was 3, 4 degrees above average and, effectively, they cooked and died.

Narrator: Increasing temperatures aren't the only threat.

As the ocean absorbs excess carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, it becomes more acidic, further weakening the coral.

Miller: It made me think, "Why don't we go and collect "every single coral species out there and create the world's first living coral biobank?"

Narrator: Each coral specimen will be taken ashore to live in a specially designed facility where it can be protected for the future.

The team are always on the lookout for new species to add to the collection.

Veron: People on this planet don't really realize that thousands of species have got some part of their life cycle in a coral reef.

When you take out coral reefs, the flow-on effect is absolutely enormous.

It's not just about corals, it's about the entire ecosystem, it's about the entire ocean.

Narrator: Coral reefs are one of the most diverse and productive ecosystems in the world.

♪ They make up less than 1% of the ocean, but support a quarter of all marine life and provide food, income, and protection from storms for around one billion people worldwide.

From fishing to tourism, reefs pump $30 billion into the global economy each year.

The Great Barrier Reef, the largest living structure on the planet, is the poster child for all that could be lost as we change the temperature and chemistry of our oceans.

Veron: At the rate that the reef is going down, we've almost passed counting in decades, we're counting in years.

So we will see the demise of coral reefs in a single human lifetime.

How incredibly dangerous is that for life on this planet?

♪ Oh, well, that was good.

The new species.

We got it.

It was really good.

That is amazing.

It is.

Well done, well done.

Yeah.

That is a great inclusion to the biobank.

That's it, eh?

Amazing.

A new species.

Good luck, number 23, you're in.

I'm not going to just, well, play bingo and think, "Oh, go to hell with the Great Barrier Reef."

No, I'm going to do all I can.

And I think this is one of the most promising projects I've ever come across.

We are doing this for the future.

We are certainly not doing it for fun.

We are doing it because we have to do it.

If we don't, what then?

It has to succeed.

If it doesn't, there's no plan B.

There really isn't.

[Laughs] Happy tears.

But that's true, yeah.

How... it's that serious, it really is.

[Singing in Maori] ♪ Stewart: A lot of our environmental knowledge is retained in waiata, in song.

And some of them are very old and, with the environmental changes, can be a little tricky to interpret.

If the fishermen are saying that that's where they're seeing life, we should go there.

OK.

I've got a paper chart here.

Narrator: Ramari Stewart is leading a voyage to find southern humpback whales, or paikea, as they are known in the Maori language of Aotearoa, New Zealand.

Whales play a vital role in maintaining the health of the oceans, something understood for centuries by her Maori ancestors.

If they're messing around in the sounds, it's anyone's guess as to what they're doing.

Narrator: Ramari is one the nation's few remaining Maori whale riders, a person with a special affinity to whales and a deep connection to nature.

Stewart: The elders used to repeat to me, "Remember, you'll know when it's your whale."

Meaning, it will come to you.

At the age of 10, I decided to take the horse for a swim.

So I'm behind the breakers, hanging on to the horse, and then, suddenly, the horse started snorting and...

It was quite scared of something and then, boof, up came this whale.

The horse swam ashore and I found myself hanging on to a whale.

The whale came to me, so I became what we call a whale rider.

Narrator: Ramari is one of New Zealand's leading Indigenous scientists.

She has a deep ancestral knowledge, and, as the climate shifts, she's keen to pass on her years of wisdom.

Look at this.

A bit of mooching around going on here, in the Little Cove.

Yeah.

Stewart: What I'm trying to create is the opportunity for a Rangatahi, a young person, to learn those observer skills that our ancestors had.

Narrator: Joining Ramari on board are Rangi and Keita.

They will study this unique environment on their week-long voyage and they can't wait to see their first whale.

I came open-minded and when I got here, been absolutely mind-blowing.

Narrator: This remote part of Aotearoa, New Zealand, is rich in wildlife.

Stewart: Perhaps even busier or more?

Maybe 9.

Narrator: It's the perfect classroom for Ramari and the new students.

Stewart: What I love is, every place I go to, there's different smells, there's different sounds.

And the sounds, before you even see a lot of them, are telling you who lives here.

And they are all important, they are all connected.

♪ Narrator: Ramari is a practitioner of matauranga Maori, a traditional way of looking at the health of entire ecosystems.

It draws on ancestral knowledge stretching back over time.

A valuable asset as the changing climate alters the natural world.

Stewart: The big thing about Indigenous knowledge is it's about similarities rather than differences.

What that means is we have the poetic license to be able to put a tree and a... and a bird and a whale, if we like, in the same family, on the understanding that there is something similar about them.

Narrator: Maori principles of guardianship or kaitiakitanga focus on the connections between all living things.

It's a part of New Zealand's marine management policy resulting in one of the world's healthiest fisheries.

[Humming] Stewart: Using waiata or song is a way of committing terms to memory.

It's how I have learned my stuff all my life.

[Speaking Maori] Once you put the names into your head, they'll always be there.

And then one day along comes a species, and it'll say to you, "Come on, you know what I am."

[Singing in Maori] Nice, yeah.

[Singing] ♪ Narrator: So far, the team has spotted lots of wildlife, but no whales.

With little time remaining, they are determined to find them.

A healthy whale population is a crucial part of Earth's carbon cycle.

Ramari wants to know if they are thriving in this remote part of the world.

Let's try and stay on that point.

Narrator: With just hours left on their voyage.

Stewart: Here they are, in front of us.

Beautiful.

You see that?

Yeah.

I didn't get it all, but I got a lot of it.

♪ See?

They are heading that way.

Narrator: The whales are on an epic journey heading down to their summer feeding grounds in the southern ocean around Antarctica.

Stewart: They are stopping off because they've found a little place to forage.

And that's exciting for us.

Narrator: This revelation will help experts protect paikea and inspire the next generation of Maori to keep their traditions alive.

Student: I feel it was just a big honor to be in this place and get so close.

It's really magical.

Narrator: Until recently, humpbacks were rarely seen here following decades of commercial whaling.

But Ramari, armed with ancestral knowledge, reveals how things used to be.

Stewart: I learned from my father the sea used to be black with baitfish.

And I said, "So, what happened?"

And he said, "Well, what do you expect?

There's no more whale tiko."

Meaning no more feces from whales, which nourished the plankton and the food chain.

That was his understanding of biodiversity.

The health of the ocean requires also a healthy population of whales and all of the species associated with... with them.

Narrator: This interconnectivity is a focus of concerted scientific study.

Its impact on the climate is far-reaching and affects us all.

When whales swim, the movement of their huge bodies mixes nutrients through the water, fertilizing microscopic phytoplankton at the base of the ocean food chain.

As phytoplankton grow, they remove 4 times more carbon from the atmosphere than the Amazon rainforest and pump out about half the oxygen that we breathe.

Stewart: Hey, look!

He's gone for it.

OK, right hand turn.

Right hand turn.

Narrator: Incorporating Indigenous knowledge into conservation efforts will help protect the whales and the surrounding ecosystem, helping it continue its vital job regulating the climate.

♪ In Australia, the coral dive team have crucial work to do.

This is more than a conservation effort.

It's a rescue mission.

Miller: The Great Barrier Reef, left to its own devices, is probably not enough to see it through the next 30, 40, 50 years.

♪ Awesome.

Look at them.

They look very happy.

Veron: What we have to do is to keep old corals going, at least in captivity.

Wait a sec!

Veron: What we are doing, in a way, is buying time.

1, 2, 3.

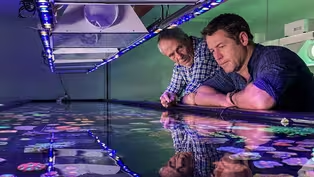

Miller: No one's ever really built a coral biobank before.

So we have to start from basically nothing.

But we can replicate everything they need in nature.

The right light, the right temperature, the right nutrients, the right water quality.

And we can have them happy and healthy.

Narrator: The goal is to collect all the coral species from the Great Barrier Reef and around the world.

Miller: This is for the ultimate conservation, their insurance policy for the future.

You know?

We know that, once they are in the biobank, they are safe.

♪ Here.

Miller: Hey, you two.

Woman: Hi.

Miller: Come on and look what Dad got.

This one is a branching coral.

Branching coral.

Can you say Acropora?

Acropora.

Good.

Now Daddy is just going to get all the water off and into the big tank.

Isla: I want to see the big tank.

Miller: Yep.

Come up and have a look.

Oh.

You mean that purple one?

There's so many different colors, isn't there?

Miller: I think I've been ignoring the idea of telling my little daughter Isla that there might not be coral reef, but she knows that everything is not beautiful and harmonious.

Wow!

What color corals can you see?

Brown, purple, black.

Miller: I have to have hope for our ability to turn this around.

Because, without hope, we are going to lose the Great Barrier Reef.

♪ Isn't that a joy to see?

Well, to me, this is the real biobank.

Isn't it?

They're on the little microchip plugs, they're entered into the database, we know what's where.

We know everything about the corals.

Where they've come from, the day they were collected.

The biobank is designed to hold these corals in perpetuity until environmental conditions improve here on the reef that we can rebuild and replant.

Or that we can use, you know, the fragments for experiments or restoration-style activities.

But here's hoping we never get to that.

Here's hoping the natural system will be resilient and strong enough to recover on its own.

As my days come to an end, I want to feel that I've tried and I've done my best.

You've got to overcome all the problems and just got to keep at it.

And that's what we're doing now.

We're going to keep at it until it's done and we won't be stopped.

[Babbling] [Laughing] Oh, my gosh, look!

Oh, beautiful shark.

Oh, Isla, look, look, look.

Big giant manta ray!

Oh, my gosh!

Miller: I'm not going to tell my daughter just yet that we haven't been able to save coral reefs, because I think we can.

I really do.

[Laughing] Woman: Wow!

That's amazing.

♪ ♪ To order this program on DVD, Visit ShopPBS, or call 1-800-PLAY-PBS This program is also available on Amazon Prime Video ♪

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: Ep3 | 6m 53s | Coral Reefs make up less than 1% of the ocean, but support a quarter of all marine life. (6m 53s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: Ep3 | 2m 45s | Seals are tagged to create a record of the increasing seawater temperature. (2m 45s)

Video has Closed Captions

Preview: Ep3 | 30s | As our oceans change, can science, nature and tradition prepare us for a fast-changing future? (30s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: Ep3 | 6m | The Comcáac Turtle Guardians are doing all they can to protect sea turtles. (6m)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship

- Science and Nature

Explore scientific discoveries on television's most acclaimed science documentary series.

- Science and Nature

Capturing the splendor of the natural world, from the African plains to the Antarctic ice.

Support for PBS provided by: